“Just an American POW”

The story of Lieutenant Colonel Harlan Chapman, USMC (ret.)

This past summer, over 4th of July weekend, I visited my parents in Vermilion, Ohio. During the visit, they introduced me to their neighbor, Harlan Chapman, who I learned was a retired Marine Corps fighter pilot and a former Vietnam Prisoner of War.

As most everyone knows, the Vietnam War was controversial to say the least and many Americans back home were vehemently against it. Regardless of anyone’s opinion on the Vietnam War, the soldiers were called to duty and went; they fought; they died; and many were held as prisoners of war for very long periods of time – under some of the worst conditions imaginable.

When the war ended and the soldiers came home, they weren’t welcomed as heroes for the sacrifices they had made and the horrors they had experienced. They were, in many cases, met with hate for serving in a war people didn’t agree with. Many experienced medical problems no one at the time seemed to understand. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) wasn’t even a diagnosis back then.

The hundreds of American POWs in Vietnam, many held for more than seven years of their lives, were forced to endure the worst of what the Viet Cong had to offer – on a regular basis. Many were beat to the edge of their lives countless times during their captivity. For most all of us – that, of course, weren’t there – it is impossible to grasp what our POWs experienced, both physically and mentally, in service to country. Hopefully, this, LtCol Harlan Chapman’s personal account of his time as a Vietnam POW, will give some perspective.

Harlan and I talked several times over the week I was home. The first time we met, I began by asking him if he was okay to talk about his time as a POW. He answered, “Aw yeah, I’m fine – it was a long time ago.” And from there, it began.

As he told me his story over the next several days, I would go home and do research on the various POW camps he was held in and the fellow POWs he would mention. Of course I had a massive amount of respect for Harlan before I had even heard a word of his story, but hearing all this in his own words caused me to gain so much more. Harlan’s words also gave me a real appreciation for the sacrifices he and all the other POWs made in answering the call to Vietnam.

Preface

I can assure you, as Harlan told me his story, he did not sensationalize it in any way. As I wrote this, I purposely went out of my way to tell his story as it was told to me – I did not add sensational words or take artistic liberties. The descriptions of Harlan’s shoot down; the various camps where Harlan was held; and the events that occurred while he was in captivity, come from Harlan’s own words, Harlan’s award citations, supplemental research, and the words of CAPT Rodney Knutson, USN (ret.), Harlan’s cellmate for over a year of his captivity in Vietnam.

When I finished the first draft of this story, I sent a copy to Harlan and his wife, Fran, for review and comment. I wanted to make sure I had captured the events and timelines accurately. Remember that I mentioned I went out of my way not to inject my own words or opinions.

A few days later I heard back from Harlan and Fran. Harlan had only a few minor comments. The most remarkable comment, to me, was not about the story – it was a note he inserted at the top of the first page, in bold, red letters just as you see it here:

(Patrick: don’t make me out as a special hero. I was just an American POW.)

With all due respect to Harlan, I disagree with this statement. I have no concept of the fear and isolation Harlan must have been feeling as he floated into a rice patty in North Vietnam on one November day in 1965, knowing that once he hit the ground, he was either going to be killed where he landed, or taken prisoner by the VC. I cannot begin to comprehend how Harlan and the other POWs endured what they did for all those years while steadfastly remaining loyal to each other and this country. I like to think that I and my shipmates would conduct ourselves in the same honorable and patriotic manner they did, but I guess you just can’t know until you are in it.

Each and every POW I researched while writing this piece lived a story similar to Harlan’s. They were shot down, captured, and tortured relentlessly for years – some more than Harlan, and some less, as he put it. But regardless, even with no end to their captivity in sight, they marched on with honor, courage, and commitment.

I have been in the Navy for over 60% of my life and I’ve never deployed longer than eight months. Harlan and the others endured extreme cruelties in service to their country, on the other side of the globe, for over seven years. I believe “American hero” is the appropriate term to describe all of these men. Or maybe as Harlan said, they are all “just American POWs.”

You can decide for yourself.

Just an American POW

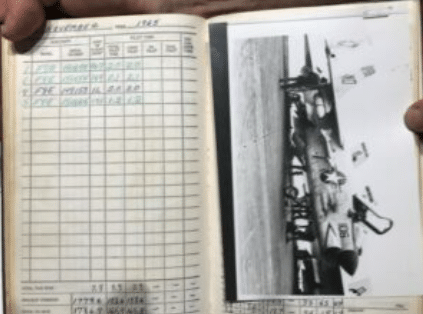

In January of 1964, Captain Harlan Chapman reported to Marine Fighter Squadron 212 based at Kaneohe Marine Corps Air Station, Hawaii. In 1965, his Squadron deployed with Carrier Air Wing 16 aboard the USS ORISKANY (CVA 34) for combat operations from the South China Sea. Harlan flew his first combat mission over Vietnam in May 1965. By November 5, 1965, he had flown approximately 100 combat missions.

Harlan’s flight log entry for November 5, 1965, with planned flight hours recorded in his log just prior to takeoff. Harlan’s F8-E Crusader on ORISKANY on the right.

Shot Down

On November 5, 1965, Harlan catapulted off the flight deck of ORISKANY in his F-8E Crusader,[1] bound for North Vietnam. He wouldn’t see the homeland again until February, 1973.

Harlan’s target was the Hai Duong, North Vietnam railroad and highway bridge. The bridge was located on a main supply route used by Russia and China to get weapons and equipment to the Viet Cong (VC). By this time, North Vietnam’s air defenses had become heavily fortified with Russian supplied SA-2 missile systems as well as light and medium anti-aircraft artillery and radar. With these Russian systems, the VC began shooting down more and more US aircraft.

Harlan’s mission called for a long, high-speed, low-level approach through heavy enemy defenses to a well-defended target deep in enemy territory where the anti-aircraft fire was most intense. He was pilot of the last aircraft of a major strike group of 32 strike aircraft on target. Harlan maneuvered his aircraft through intense and lethal anti-aircraft fire, dived on the target, and delivered his bombs on the bridge. Witnesses observed Harlan’s aircraft pulling off target and exploding in the air after direct hits from the lethal enemy fire. He was then observed descending in his parachute, apparently unhurt, into a densely populated and heavily defended area adjacent to Hai Duong.[2]

Now 84 years old, Harlan remembers that day as if it happened yesterday. Sitting in his living room nearly 54 years later, he recounted his memories of the day he was shot down, “I felt a thud and a few seconds after that I lost all control of the aircraft. The plane was spinning out of control and the G’s were so great that I couldn’t raise my arms up to reach the ejection handles. At that point, I was sure I was going to die. I don’t know if I got knocked out or if I passed out, but the next memory I have is floating in the air under my parachute. There is another ejection handle under the seat and maybe I pulled that one, but I don’t have any recollection of how I ejected.” Harlan continued, “On the way down, I could feel my shoulder was dislocated. I could hear bullets whizzing past me—they shot at me all the way down. Eventually, I landed in a rice patty and stuck in the mud. I was in it up to my knees.”

I asked Harlan if he had any chance of getting away. He said, “No, there were VC all around.” I asked how close they were. He laughed, “Well, they helped me out of the mud.” This is how Harlan’s seven years, three months, and seven days in captivity began.

The VC stripped Harlan down to his underwear and put him in a jeep. About an hour later, he arrived at Hỏa Lò Prison, known as the Hanoi Hilton,[3] as the 49th American POW of the Vietnam War. It was still light outside.

Captivity

“It would be difficult, if not impossible, to relate the treatment of over seven years of captivity in the space allotted. However, I can sum up my opinion of the treatment by saying it was basically cruel. While in captivity, I was tortured many times, using ropes, cuffs, isolation, and beatings.”

– Harlan Chapman

At the Hanoi Hilton, the VC cuffed Harlan’s arms behind his back; put him in leg irons; and then placed him in a locked room alone. With his dislocated shoulder and his arms in this position, the pain in Harlan’s shoulder became intense. He was left alone for approximately an hour before his captors finally entered the room. Harlan was sitting on the floor, his captors were sitting in chairs.

Harlan’s interrogators demanded information about his mission. He responded with his name, rank, and serial number as required by the Code of Conduct. The questions continued, but Harlan’s answer remained the same. He refused to give any information and this angered his interrogators.

In Harlan’s words, “I wasn’t giving them any information. They roughed me up pretty good, punching and slapping me. Then they had someone come in and tighten the cuffs on my arms and pull them up higher and higher. The pain was excruciating. The interrogation went on for hours. Every so often, they would make the cuffs on my arms a little tighter. The physical beatings went on and off the entire time. They knew I was a Marine, but they didn’t understand why I was with the Navy. They asked me what the Navy’s mission was and I said, I don’t know, I’m a Marine. Then they asked me what the Marines’ mission was and I said, I don’t know because I’m with the Navy right now. I was ducking the questions as best I could. They pointed a pistol to my head and threatened to shoot me. When they finally decided I didn’t have any information on the mission, they demanded names of pilots in my squadron. I gave them two names: Captain Marvel and Dick Tracy. This seemed to satisfy them for the moment. They stopped the interrogation and put me in a cell. I felt terrible. I felt that I had failed my country because the enemy broke me. Even though I gave them fake information, I still gave them information. They broke me.”

Another POW, Air Force pilot Lt. Lee Ellis, described this VC torture technique, “After the prisoner’s legs were tied together, his arms were laced tightly behind his back until the elbows touched and the shoulders were virtually pulled out of joint. Then the torturer would push the bound arms up and over the head, while applying pressure with a knee to the victim. During this torture, the circulation is cut off and the limbs go to sleep, but the joint pain continues to increase as the ligaments and muscles tear. When the ropes are finally removed, circulation surges back into the ‘dead’ limbs, causing excruciating pain.”[5]

After this initial interrogation, the VC put Harlan in a temporary holding facility. There were eight cellblocks with one POW in each block. Prisoners were strictly prohibited from talking to each other, but could get away with some quiet talk during “rest hour” when the guards would take naps each day. The POWs were fed small amounts of rice, bread, and soup. Each prisoner had a water cup that he would have to hold out through an opening in his cell for the guards to fill. Harlan recalled the first time he held his water cup out for refill, “I was holding my cup out and the guard dumped an entire pitcher of boiling water all over my hand and arm. Needless to say, I didn’t make that mistake again.” At this camp, the guards regularly beat the prisoners.

Harlan spent approximately four to six weeks in the temporary holding facility and during this time, he was able to learn the prisoner tap code. He also made contact with his Wing Commander from ORISKANY, CDR James Stockdale. Stockdale had been shot down a little less than a month before. Sometime later, Stockdale would be permitted to write letters home and was able get Harlan’s POW status back to the US Government. This was the first proof of life for Harlan’s wife and son. From this facility, Harlan was transferred to the camp known as “The Zoo.”

The Zoo

The Zoo was located in Hanoi about 2.5 miles SW of the Hanoi Hilton. There were 8 buildings that housed prisoners. Harlan could remember the names the prisoners gave to 6 of the buildings: the Pool Hall, the Pig Sty, the Office, the Barn, the Garage, and the Auditorium.” There was a building in the camp with a kitchen and VC admin offices.

Conditions at the Zoo were notoriously bad, even by North Vietnamese prison standards. There were loudspeakers throughout the camp that blared anti-American and anti-war propaganda throughout the day and night.

When Harlan arrived at the Zoo, the VC immediately placed him in solitary confinement. His cell had four walls, a door with no window, a light, and a bucket for a toilet. The prisoners slept on the floor in solitary. The guards kept the lights on 24 hours a day inside each of the solitary cells and the only sounds Harlan could hear were the loudspeakers around the camp blaring propaganda in the morning and then again in the evening for about a half hour each time. During this time, CDR Jeremiah Denton[6] was placed in the cell next to Harlan’s. CDR Denton had been a prisoner for more than six months and knew how to communicate using the prisoner tap code.[7] He taught Harlan the code and a method for Harlan to teach other prisoners once out of solitary.

After learning the code, while still in solitary, Harlan took great personal risk to teach each new POW that wound up in either of the cells adjacent to his. If a prisoner was caught communicating with another prisoner, in any way, the consequences were stark.

On October 17, 1965, just 19 days before Harlan was shot down, LTJG Rod Knutson, a Naval Flight Officer and former enlisted Marine, was flying his 76th combat mission over Vietnam from the USS INDPENDENCE. His F-4B Phantom, flown by ENS Ralph Gaither, was hit and the two were forced to eject.

Rod Knutson and ENS Gaither were both captured by the VC. Rod recalled the events leading to his capture, “Due to my low altitude ejection at over 500 knots, I suffered a fractured neck and back. During my capture I was fired upon by enemy soldiers and to protect myself I killed two of them before I was knocked unconscious by the muzzle blast of a rifle being fired at point blank range. I had a laceration over my right eye and an abrasion down my face along my nose, powder burns on my face, and a swollen knee.” [8]

As with Harlan, Rod spent time 4-6 weeks at the Hanoi Hilton before he was eventually moved to the Zoo. Upon his arrival, Rod was immediately placed in solitary confinement.

In May of 1966, after six to seven months in solitary confinement, Harlan and Rod, who were still complete strangers to each other at the time, were moved out of solitary and placed together in a regular cell in the building known as the Office. They spent about a month together at the Zoo before being moved together to the camp known as the Briarpatch. Harlan described this new location as “rural.” He made it a point to mention the camp had no electricity. I asked what the significance of this fact was and he replied, “I didn’t have to listen to loudspeakers blaring propaganda anymore!”

At Briarpatch, Harlan and Rod shared a cell in three different buildings from June of 1966 until late January, 1967. At the Briarpatch, Harlan and Rod immediately began establishing the groundwork to get the prisoner tap code they had learned at Hỏa Lò out to as many prisoners as he could. They worked tirelessly to create a network that would ensure the code propagated throughout the entire camp. Harlan and Rod not only taught other POWs the code, but also gave them a non-verbal method for teaching others. Soon, new POWs were being taught the code within days of their arrival at the camp. Harlan recognized the vital importance of maintaining open lines of communication between prisoners and disregarded his own well-being to ensure the welfare of his fellow POW’s

Harlan’s dedication to his fellow POWs, and his disregard for his own well-being, eventually caught up with him. In July of 1966, the guards caught Harlan communicating with a fellow POW in another room. They immediately took Harlan from his cell to another location in the camp where they beat and tortured him for two days. At the end of the second day, the guards bound Harlan’s wrists and arms behind his back with cuffs and rope and left him this way in solitary confinement for five days.

On this fifth day, the guards brought Harlan back to his cell, still in bindings. During this time, Rod fed Harlan; brushed Harlan’s teeth; washed Harlan; and helped Harlan with his toiletries when he had to go to the bathroom. After being bound continuously for 10 days, the guards finally removed Harlan’s bindings.

In captivity, the POWs kept track of time through the tap code; the VC change in routine on the weekends; and the propaganda broadcasts which would sometimes mention dates. They exercised in their cells when they could. The prisoners were not given books or anything else to read, although, Harlan remembers a couple of occasions where he was given English language North Korean propaganda magazines. The magazines were dedicated to the glorification of North Korean leader Kim Il-Sung. Harlan found humor in these magazines. The prisoners were not permitted to send or receive mail or packages at the Briarpatch or the Zoo. During Harlan and Rod’s first Christmas together in captivity, Harlan remembers, “We promised each other ‘if-we-ever-get-home’ Christmas gifts. For our first Christmas after release, Rod sent me the Zippo lighter he had promised back in 1966 with the inscription, FUCK COMMUNISM.”

In January of 1967, the VC moved Harlan and Rod back to the Zoo. They shared a cell in the Barn and continued to teach the tap code to as many of their fellow POWs as they could. One such POW was Navy Seaman Apprentice Doug Higdahl.[9] Doug had fallen off of his ship in the Gulf of Tonkin and was picked up by Vietnamese fisherman after 12 hours in the water. The fisherman turned him over to the VC and he eventually ended up at the Zoo. During his time as a POW, Doug managed to memorize the names and other personal data of 256 other prisoners. He was later ordered by the senior officer in the camp to take an early parole offered by the VC and get all of the names he’d memorized back to the US Government for proof of life. When Doug arrived back in the US, he was able to provide all 256 names.

In late January 1967, Harlan and Rod were severely tortured after refusing to bow to some guards that had entered their cell. They were put in leg irons and their hands were cuffed to their bed boards. The guards kept Harlan and Rod in these bindings 24 hours a day for nearly 30 days, “living in their own filth,” as Rod described it.

In May of 1967, after a little over a year of being cellmates, Harlan and Rod were split up. They didn’t see each other again until almost six years later.

Harlan stayed at the Zoo and the VC continued to interrogate him on a regular basis. During these interrogations, they used severe torture methods, such as rope bindings, irons, beatings, and prolonged isolation. The torture and severe maltreatment continued all the way through October of 1967 when Harlan was finally moved from the Zoo to another camp. Through all these interrogations, Harlan adhered to the Code of Conduct, steadfastly refusing to provide the enemy with any important information – not even his own biographical information. Each time he refused to provide information, he did so knowing he was inviting harsher treatment on himself. Harlan credits his fellow POWs with giving him hope and inspiring him to continue on during those extremely difficult times while he interned at the Zoo.[10]

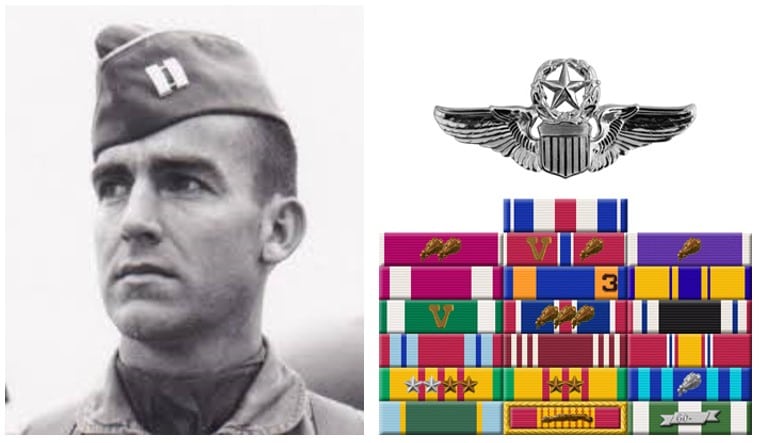

When Harlan arrived at his new camp in October of 1967, he was put into a cell with Capt. Thomas Pyle, an Air Force navigator, and two Air Force pilots, Capt. Wilford “Will” Abbot and Capt. Douglas “Pete” Peterson.[11] The four spent the next 3.5 years together in the same room, with no windows (except a pass through window for food and water), concrete slabs for beds, and one bare lightbulb. Security remained tight at all the camps in Vietnam. After over five years in captivity, Harlan had had open communications with only four other POWs – Tom, Will, Pete, and Rod.

I asked Harlan if he or any of his fellow POWs ever attempted to escape. He said there were not a lot of opportunities, but some tried, “Some POWs from another camp tried to escape. They were eventually re-captured. The VC response was to beat the escapees and, all the senior officers in the camp. The beatings were so severe that two of the POWs died from their injuries – one of the senior officer and one of the POWs that had tried to escape. Word of the deaths got around to the other camps and after that, leadership in each camp passed word that no one would attempt to escape unless there was outside support.”

Things slowly began to get a little better for Harlan in late 1970. For the first time, after five years of captivity, he was permitted to send and receive letters. Harlan sent a letter to his wife and son – the first communication with his family since he was shot down.

In November of 1970, US Special Forces executed Operation Ivory Coast, a raid on the Son Tay prison camp located 23 miles west of Hanoi. The purpose of the raid was to extract the 61 POWs being held at the camp. The assault on the camp went as planned; however, after taking the camp, U.S. forces learned that the POWs had been moved previously for reasons unrelated to the raid. After the raid, the VC worried more raids like Son Tay were coming and began conducting drills with the POWs to prepare. Harlan described one of the drills, “It was nighttime. They cuffed our arms behind our backs and took us out into the boonies, far away from the camp. We were put in small, one-man holes that had been dug in the ground. We weren’t allowed to move or make noise. At some point, a huge ant crawled into my ear. There was nothing I could do. I kept trying to shake it out, but nothing worked. We were in our holes for hours. It was one of my worst nights as a POW. I later got the ant out. After the drill, they took us back to the camp and finally removed our arm cuffs.

Next, Harlan was moved to a camp named Dogpatch, near the Chinese border, where there were about 200 POWs. He spent several months at this camp until the VC closed it down and sent him back to Hanoi.

Prisoner Release

It was now mid-1972 and things had changed a lot since Harlan was last in Hanoi. He described his return to Hỏa Lò Prison, “We were all put into a big room. There were about 50 of us. There, they split us up and assigned us to four different rooms with about 15 POWs living in each. We were allowed to talk to each other and there were whispers that we could be released in the near future.” Harlan said there were signs the war may be winding down, “The constant bombing had pretty much stopped. Generally, we were treated significantly better. We were given new clothes and mats to sleep on with mosquito nets. The food was better. The guards’ attitudes towards us got better. POW’s were allowed to teach Spanish and math classes. We were free to walk around the camp. Things like that. We knew the peace talks were going on, but the VC kept extending the talks and things were moving slowly. In late 1972, word from higher was passed around the camp that none of the POWs should ‘act up’ because release may be imminent.” Harlan continued, “Then one day, a month or so later, the VC assembled all of us in the big room and read us the Paris Peace Accord. This is when we really starting thinking it (release) was going to happen.”

The Paris Peace Accord was a peace treaty signed on January 27, 1973. The goal of the treaty was to end the war and establish peace in Vietnam. The treaty called for the removal of essentially all remaining US Forces, including air and naval forces, in exchange for the return of Hanoi’s POWs. It also ended direct U.S. military intervention in the conflict. The war between North and South Vietnam would temporarily stop, but for less than a day. Two years later, a massive North Vietnamese offensive conquered South Vietnam.[12]

The prisoners got word that release was now imminent. When it happened, they would be released in three phases. The POW code dictated the order in which the POWs would be released. The first to go were the sick and wounded. After that, those that had been POWs the longest (first in, first out) would fill the remaining numbers. In this case, the first out were those POWs that had been in captivity for 6-8 years. Harlan and Rod Knutson were both part of the first three groups to go. On February 12, 1973, without notice, the VC marched Harlan and the rest of the first group of POWs to an airfield. The group was put in formation and stood waiting. Harlan recalled, “We weren’t sure what was happening. Then, we saw a plane. As it got closer, we realized it was a military aircraft – a Lockheed Martin C-141 Starlifter. We were loaded on the plane and flown out of Vietnam.” This was the second of three flights out that day in support of Operation Homecoming – Rod was on the first. Over the next month and a half, Operation Homecoming brought the remaining 591 American POWs home from Vietnam.

Homecoming

After spending 2,657 days in captivity, and now 45 pounds lighter, Harlan was a free man.

Harlan’s plane landed at Clark Air Force base in Angeles City, Republic of the Philippines. There, he and the other POWs received brief medical examinations and each was assigned an escort officer to help him decompress. The escort officers had files with family letters and updated photographs, they answered questions about the past seven plus years and escorted the men through debriefings all the way back home. The men were allowed time for a visit to the Base Exchange. For his first act as a free man, Harlan bought ice cream. The POWs were also given the opportunity to call home. Harlan called his wife. During this call, she told him that their relationship was over – she had left him, “I couldn’t blame her. We had been married for 12 years and with my deployment to Japan, my time in captivity, etc., I had been gone about 9 of our 12 years of marriage. That is a lot to ask of anyone.” From there, they flew to Hawaii for a brief stopover.

The POWs received a warm reception in Hawaii. All the Generals and Admirals on the island gathered on the airstrip to welcome the men home. As the POWs went through the receiving line, Harlan recalled General Louis Wilson,[13] Commander, Fleet Marine Force Pacific, shook his hand and said, “Welcome back to the Marine Corps!” Harlan replied, “Thank you, General, but I never left.” Harlan, a Captain when he was shot down, also learned that he had been promoted twice while he was in captivity and was now a Lieutenant Colonel.

The group departed Hawaii and on February 14, 1973, landed at Travis Air Force Base about 50 miles outside of San Francisco, CA. Because the release happened quickly, and with little notice, Harlan’s family was not able to get to California in time to meet him when his plane landed. Later that day, he was taken to a hospital in Oakland for medical observation and debriefing.

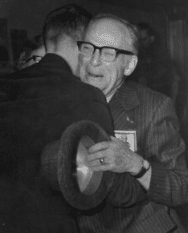

The next day, Harlan’s parents and siblings, along with his son, “Har,” came to the hospital to welcome him home. Har, now 13 years old, was five the last time he had seen his father, “He didn’t know me. We were basically strangers. He and I exchanged awkward hellos with my other family members around. Sometime after I finished all of my medical exams and debriefings, Har visited me in Ohio and we took off on a trip to Europe for a couple of months so we could get to know each other. We went all over Western Europe and sailed the coast of Norway. It was good for us.”

Harlan meeting his parents in Oakland 2/15/73 for the first time. Footnote from Fran: “I have always thought this picture of Harlan with his Dad, Thayer, taken at their reunion, spoke volumes. His dad died 6 months later. I truly believe he was determined to see his son again.”

During his time in the hospital, Harlan was asked how he was able to endure the cruel treatment and isolation all those years in captivity, “I am very fortunate to have wonderful parents who love America dearly and appreciate how great this country is. Through their insight, patriotism came very easy to me. I am proud to be an American and proud to serve my country as a Marine. This pride and love for my country was the main force that kept me going through the long years of imprisonment … After having lived in a communist environment for an extended period, I now, more than ever, appreciate the freedom and opportunity that the United States of America offers to its citizens.”

Fran

Harlan spent several weeks in hospitals in Colorado and Oakland for medical evaluation, debriefing, and R & R. A month after he arrived in California, Harlan took a pass from the hospital in Oakland to go visit his parents and sister in Colorado for a few days. On this trip, Harlan met Fran, his future wife, “My Mom & Dad had flown to my sister’s place in Littleton, CO. I flew there to spend a few days with them, accompanied by my escort officer, Bob Short, USAF. We went to a restaurant in the Colorado foothills with the entire family. My niece, Shelle, didn’t want me to be the only person there without an escort, so she invited her friend and co-worker Fran to join us. After dinner that evening we watched TV coverage of the second group of POWs arriving in California.”

After that meeting, Harlan and Fran became close friends and talked on the phone frequently. A few months later, Harlan asked Fran out for a date. For their first date, Harlan flew Fran to San Francisco to attend a special dinner for the POWs. The dinner was hosted by Governor Ronald Reagan and his wife Nancy at the California Governor’s mansion. Harlan smiled, “It was a pretty good first date.” On Sunday of that weekend, Harlan and Fran were having breakfast & reading the paper when they saw a notice that President Nixon was going to have all the POW’s visit the White House. On May 24, 1973, Harlan and Fran met the President.

In June of 1973, Harlan and his son went to Europe together. When they returned, Harlan had to go back to Oakland for some final checkups before beginning his refresher flight training. Late in the summer that year, Harlan went back to Colorado to visit Fran. He invited his old cell mate and close friend, Rod Knutson, to join him. During the visit, Fran introduced Rod to her best friend, and Harlan’s niece, Shelle. Rod and Shelle would marry the following April with Fran serving as the maid of honor. A month later, Harlan and Fran married, with Shelle serving as the maid of honor.

Back to the Fleet

By September of 1973, Harlan was ready and cleared to get back to flying. In October of 1973, he reported to the F4 training squadron and began his re-qualification. In July of 1974, following refresher flight training, Harlan took command of Marine Fighter/Attack Squadron 314 (VMFA-314) at MCAS El Toro. He served in this position until his retirement from the Marine Corps on July 31, 1976.

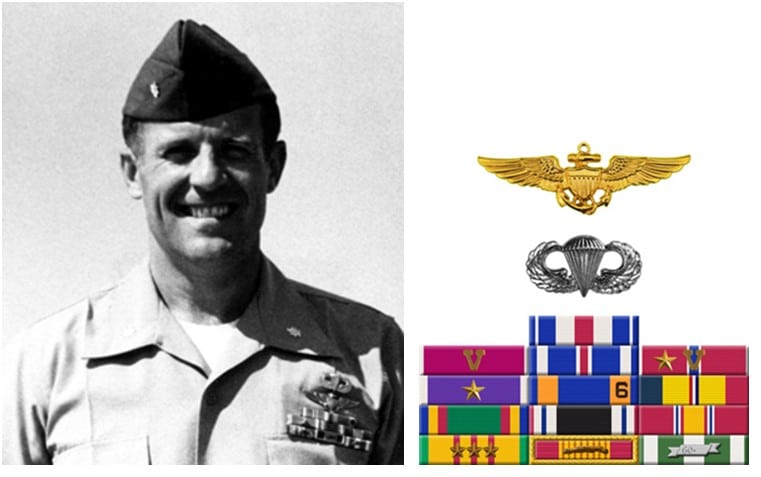

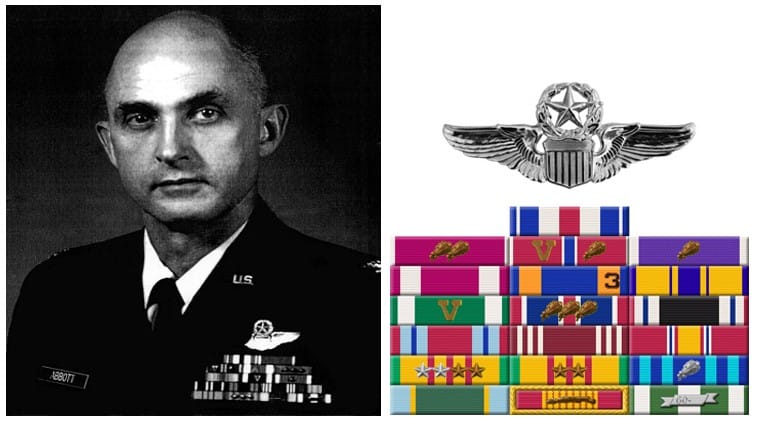

Lt Col Harlan Chapman, USMC (ret.) is entitled to wear the following: Silver Star, Legion of Merit (w/Combat V), Distinguished Flying Cross, Bronze Star (w/Combat V, gold star in lieu of 2nd award), Purple Heart (w/gold star in lieu of 2nd award), Air Medal (w/6 in lieu of 7th award), Combat Action Ribbon, Prisoner of War Medal, and various unit and campaign awards.

Life after the Marine Corps

After retiring from the Marines, Harlan and his family went back to Ohio, “We moved into the old Victorian farmhouse my Great Grandfather (also Harlan Page Chapman), who had taken a ball in the hip during the Civil War, built in the 1880’s. I attended the local junior college to catch my breath and figure out what I wanted to do. I took real estate classes, but it was soon obvious that I didn’t have a salesman’s personality, or the desire to work nights & weekends, which the job required. But the classes and contacts lead me to a friend who was a real estate appraiser and WWII vet. He mentored me as I studied real estate appraisal.”

Harlan eventually got his residential and commercial real estate appraisal licenses. Fran followed Harlan into the field and together, they started a small appraisal business which they ran for over 25 years. Harlan said, “I didn’t get us rich, but being self-employed did allow me the freedom I personally needed. I retired completely when I qualified for Social Security in 1999.”

POW Network

The first time all of the POWs got together was when President Nixon had them all to the White House in 1973. There were several other high-profile reunions in the next few years, including one held by Ross Perot in TX, which Harlan was unable to attend. The reunions eventually settled into roughly a five year cycle until about the 30th. After that, they became more frequent as the group began losing members more often. The POW network developed over the years into websites and email distributions where many of the men keep in touch.

These days, Harlan is not able to travel to all of the reunions, but he does stay in touch with several of the men from his days in captivity. As noted, Rod Knutson and Harlan became relatives and still see each other frequently, “On a personal basis, in addition to Rod, I have maintained a close emotional tie with two of my long-term cell mates – Will Abbott, who now lives on Coronado, California, and Tom Pyle, who lives in North Carolina. Our 3rd cell mate, Doug ‘Pete’ Peterson, who later became the first Ambassador to Vietnam, now resides in Australia. We hear from ‘Pete’ every Christmas.”

Return to Vietnam

In April of 1997, Pete Peterson was appointed the first United States Ambassador to Vietnam. Later that year, Will Abbott contacted Harlan about potentially planning a trip to go visit Pete in Hanoi. They worked out the details over the next couple of months and in February 1998, the three of them, with their wives, went back to Vietnam. On the way there, they stopped in Beijing to visit another POW friend, BGEN Jon Reynolds USAF (ret.), who was then the president of Raytheon China.

Once in Hanoi, they joined up with Pete and over the next few weeks, visited many of the sites that changed their lives forever over 25 years ago. Seeing these places evoked a lot of different emotions for Harlan, “ The three of us former cell mates visited the “Hanoi Hilton” with our wives. We mostly hid the emotional impact it had on us with bravado humor, remembrances of time spent there, and comments on how it no longer smelled, etc. Seeing the concrete slabs where we slept in leg irons & manacles and the cells with the manacles still in the walls seemed hardest on Will’s wife who said she had spent six years trying her hardest not to imagine these things while raising her two sons. Half of the Hỏa Lò prison complex been torn down to make space for a new hotel, the remainder was converted into a museum to the many wars Vietnam had endured. We also visited the Zoo where the three of us had spent over three years together.”

In late 1998, Harlan and Fran visited Vietnam a second time, “On our second visit to Vietnam, we went as part of a small group tour of about 8-10 POWs. I invited my son Har and his wife Liz to accompany us on this trip. During the tour, I was able to see the site where I was shot down in North Vietnam. Har and I walked the bridge between Haiphong and Hanoi that had been my target on 11/5/65. We traveled from rural areas near the China border all the way to Saigon.”

Today

Harlan and Fran eventually settled in a condominium complex that sits right on the shores of Lake Erie in Vermilion, Ohio. In the summers, you can see them out on their back patio enjoying their amazing view of the lake. Rod and Shelle have a home in Montana, but spend about half of the year touring the country in their RV.

Harlan, thanks for sharing your story with me. You are a true American hero!

[1] Between 1964 and 1972, 83 Crusaders were either lost or destroyed by enemy fire. Another 109 required major rebuilding. 145 Crusader pilots were recovered; 57 were not. 20 of the 57 were captured and eventually released. The other 37 remained missing at the end of the war. (See WE CAME HOME, Captain and Mrs. Frederic A Wyatt (USNR Ret), © 1977)

[2] This paragraph contains excerpts from Lieutenant Colonel [then Captain] Harlan Page Chapman’s Distinguished Flying Cross award citation for his actions during the Vietnam War.

[3] POWs arriving in Hanoi normally were moved directly to the Hanoi Hilton, a maximum security prison built in the heart of the city by the French in the early 1900’s. It was divided into three parts: (1) “New Guy Village,” called “Heartbreak” which served as the interrogation facility during the war from 1965 to late 1971, (2) “Little Vegas;” and (3) “Camp Unity,” the largest section first used to detain Americans in 1970.

[5] See “Leading with Honor” by Lee Ellis © 2012

[6] Denton is best known from this period of his life for the 1966 televised press conference in which he was forced to participate as an American POW by his North Vietnamese captors. He used the opportunity to send a distress message confirming for the first time to the U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence and Americans that American POWs were being tortured in North Vietnam. He repeatedly blinked his eyes in Morse code during the interview, spelling out “T-O-R-T-U-R-E”. (See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jeremiah_Denton)

[7] Capt. Carlyle S. “Smitty” Harris, USAF, Capt. Carlyle S. “Smitty” Harris, is credited with bringing the code to Vietnam. He initially taught three men in his cell at the Hanoi Hilton the TAP code which was a communication method used by British Royal Air Force pilots during World War II. This led to the POWs ability to communicate and organize inside of the camps. They risked their lives to teach incoming captives about the code, to continue the organization and communication throughout the war. The TAP code brought a chain of command to the camps and helped the POWs keep their morale up and to keep secrets from the enemy. (See “Smitty” Harris motivates 18-06 with his story, https://www.columbus.af.mil/News/Article-Display/Article/1468649/smitty-harris-motivates-18-06-with-his-story/ )

[8] See KNUTSON, RODNEY ALLEN, POW Network Bio, https://www.pownetwork.org/bios/k/k048.htm

[9] “The Incredibly Stupid One,” CAPT Dick Stratton. See https://www.pownetwork.org/bios/h/h135.htm

[10] This paragraph contains excerpts from Lieutenant Colonel Harlan Chapman’s Silver Star award citation for his actions during the Vietnam War.

[11] Douglas “Pete” Peterson spent over six years as a prisoner of the North Vietnamese army after his plane was shot down. He returned to Hanoi when he became the first United States Ambassador to Vietnam in 1997. He was the ambassador to Vietnam until July 2001. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pete_Peterson

[12] See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paris_Peace_Accords

[13] Louis Hugh Wilson Jr. was a general in the United States Marine Corps and a World War II recipient of the Medal of Honor for his actions during the Battle of Guam. He served as the 26th Commandant of the Marine Corps from 1975 until his retirement from the Marine Corps in 1979, after 38 years of service. (See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Louis_H._Wilson_Jr.)

Harlan and his fellow POWs from back in the day!