The Vietnam War, often referred to as the “Second Indochina War,” spanned two decades (1955-1975) and became one of the most politically charged, controversial, and transformative events of the 20th century. It not only changed the course of Vietnamese history but also deeply influenced American politics, society, and foreign policy. This essay provides a comprehensive overview of the Vietnam War, examining its causes, major events, and long-lasting ramifications.

Historical Context and Causes

To understand the Vietnam War, one must delve into the history of Vietnam’s relationship with foreign powers. From the mid-19th century until WWII, Vietnam was a French colony. However, during WWII, Japanese forces took control of the region. After Japan’s defeat in 1945, the Viet Minh (a communist and nationalist movement) led by Ho Chi Minh declared Vietnam’s independence. This act initiated the First Indochina War against the French who sought to reclaim their colonial possession.

The war culminated in the 1954 Battle of Dien Bien Phu, resulting in French defeat and leading to the Geneva Accords, which temporarily partitioned Vietnam at the 17th parallel: the North held by communists and the South by anti-communists.

However, the division was not merely geographical; it was emblematic of a broader Cold War rivalry. The United States, alarmed by the spread of communism in the wake of the Korean War and influenced by the ‘Domino Theory’ (the idea that if one country in a region turned communist, then others would follow), started offering military aid to the anti-communist government in South Vietnam.

By the early 1960s, the situation in South Vietnam was deteriorating. The North, with support from the Soviet Union and China, sought reunification with the South and endorsed a guerrilla campaign by the Viet Cong (a communist-aligned group in the South) against the South Vietnamese government.

U.S. involvement escalated under President Lyndon B. Johnson after the 1964 Gulf of Tonkin incident, leading to large-scale U.S. military deployment. Bombing campaigns, such as Operation Rolling Thunder, were initiated, and by 1969, over half a million American troops were stationed in Vietnam.

However, the North’s guerrilla tactics, the unfamiliar jungle terrain, and the lack of clear military objectives made the conflict particularly challenging for the U.S. forces. Despite possessing advanced military technology and conducting large-scale operations like the Tet Offensive in 1968, victory remained elusive.

As the war dragged on with mounting U.S. casualties and no end in sight, it became increasingly unpopular domestically. Graphic media coverage, the conscription system, and incidents like the My Lai massacre fueled anti-war sentiments. College campuses became hotbeds for protests, culminating in events like the shooting at Kent State University in 1970.

Concurrently, the Civil Rights Movement intertwined with anti-war sentiments. Prominent figures like Martin Luther King Jr. spoke against the war, linking the injustice abroad to racial and economic inequality at home.

By the early 1970s, the American public’s weariness of the war, coupled with the exposure of government deceit in the Pentagon Papers, compelled a change in policy. President Richard Nixon, who had inherited the war, initiated a strategy termed “Vietnamization,” aiming to gradually withdraw U.S. troops while bolstering the South Vietnamese army.

Concurrently, peace negotiations began, culminating in the 1973 Paris Peace Accords. These accords led to a ceasefire and the withdrawal of all U.S. combat troops, though American military aid continued to the South.

Despite the accords, fighting resumed between North and South Vietnam, and without American military support, the South’s capital, Saigon, fell to the North in 1975, leading to the country’s reunification under communist rule.

The repercussions of the Vietnam War were manifold:

1. For the U.S: Over 58,000 Americans died, with many more physically and psychologically traumatized. The war brought societal divisions to the fore, shattered the public’s trust in its leadership, and shaped a more cautious American approach to Cold War confrontations.

2. For Vietnam: The human toll was immense, with estimates suggesting millions of military and civilian casualties. The country’s infrastructure was devastated, and the environmental impact, particularly due to the use of Agent Orange, had long-term health consequences for the Vietnamese population.

3. Internationally: The war exposed the limitations of superpower interventions and indicated a shift in the global balance of power, signaling the decline of Western dominance and the rise of Asian counterparts.

In conclusion, the Vietnam War remains a potent symbol of the perils of military intervention, the complexities of global politics, and the deep scars – both physical and psychological – that such conflicts can inflict on nations and individuals alike. The war’s lessons continue to resonate today, serving as a cautionary tale for future generations.

Introduction to the Air War

When the U.S. increased its military intervention in Vietnam in the mid-1960s, it brought superior air power to the conflict. The U.S. believed that through strategic bombing campaigns, it could pressure North Vietnam into abandoning its support for the communist insurgency in South Vietnam.

Key Aspects of the Air War

The air war in Vietnam was not without significant challenges:

The air war’s legacy during the Vietnam War is multifaceted:

In conclusion, the air war during the Vietnam War was not merely a display of superior air power. It was a complex, evolving campaign that reflected the broader challenges of the conflict. While it showcased technological advancements and tactical innovations, it also exposed the limitations of air power against a determined, adaptive enemy in a complex geopolitical environment.

The Vietnam War marked a significant period in aviation history. With the intensity and duration of the conflict, both the United States and North Vietnam suffered substantial combat aircraft losses, a testament to the fierce aerial combat, the advancements in anti-aircraft and missile technology, and the strategic importance of air superiority in modern warfare.

U.S. Aircraft Losses

The North Vietnamese Air Force (VPAF) was considerably smaller and less technologically advanced than its U.S. counterpart. However, they used their assets effectively, often in defensive roles.

Conclusion

The aircraft losses during the Vietnam War underscore the risks and challenges of aerial combat, especially in a conflict marked by technological advancements and evolving tactics. The war led to changes in aircraft design, pilot training, and aerial combat doctrine, with lessons from Vietnam shaping subsequent generations of aerial warfare. The loss of aircraft, and more importantly, the pilots and crew members, remains a poignant reminder of the human costs associated with war.

The Vietnam War, which raged from 1955 to 1975, was one of the most divisive conflicts in U.S. history. It pitted the communist forces of North Vietnam and the Viet Cong against the U.S.-backed government of South Vietnam. Amidst the broader canvas of this controversial war, the experiences of American prisoners of war (POWs) in Vietnam are both haunting and remarkable. This essay delves deep into the U.S. POW experience during the Vietnam War, exploring their capture, imprisonment, resilience, and the long road to repatriation.

The plight of U.S. POWs in Vietnam began with their capture on the battlefield. American soldiers, pilots, and sailors were captured by both North Vietnamese regular forces and the Viet Cong guerrillas. This often happened under dire circumstances – during helicopter crashes, when troops were ambushed, or when pilots were shot down. Once captured, they were forced to endure a grueling journey through the jungles of Vietnam to reach various prison camps.

Many American POWs were initially held in makeshift jungle prisons. These early days were often the harshest, as they faced immediate interrogation. The North Vietnamese and Viet Cong forces were eager to extract military information and use the prisoners for propaganda purposes.

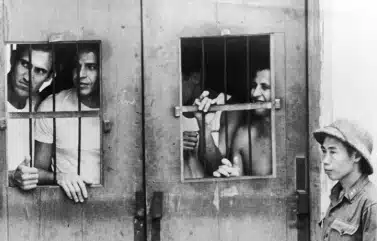

One of the most notorious prison facilities was Hoa Lo Prison, located in Hanoi, which the American POWs derisively referred to as the “Hanoi Hilton.” This prison housed both American pilots and other prisoners, and it would become infamous for its harsh conditions and the mistreatment endured by its inmates.

Beyond the Hanoi Hilton, numerous other prison camps were scattered throughout North Vietnam, often located in remote areas to evade aerial surveillance or rescue attempts. These camps ranged in size and conditions, but they all shared the grim reality of captivity in an enemy land.

The North Vietnamese and Viet Cong often used brutal tactics against their American POWs. These tactics were justified by labeling the prisoners as “criminals” rather than acknowledging their status as POWs under the Geneva Convention. This label provided a thin veneer of legitimacy for the use of torture and intense interrogation.

The methods of torture were horrifying. POWs endured beatings, rope bindings, extended periods of solitary confinement, and even mock executions. The North Vietnamese captors aimed not only to extract military information but also to break the prisoners’ spirits and use them for propaganda. Many American POWs were coerced into making anti-American statements or confessions of wrongdoing. However, most resisted by providing misinformation or remaining as vague as possible.

The POWs developed a complex system of covert communication to support one another during these dark times. Through tapping on cell walls in a special code or using subtle hand signals, they shared information and offered encouragement. This secret communication was not only vital for morale but also served to ensure that the prisoners maintained a consistent story during interrogations.

In the prison camps, the daily life of American POWs was marked by monotony and extreme hardship. Malnutrition was rampant due to inadequate food supplies, and many prisoners suffered from a lack of medical care. Sanitary conditions were often abysmal.

Yet, amid these dire circumstances, the human spirit’s resilience shone through. The POWs found ways to cope with their conditions and offer each other support. They shared stories of home, sang songs, and even held clandestine religious services to maintain their faith.

Religion played a significant role in many prisoners’ lives. Whether through prayer, meditation, or simply maintaining a sense of hope, faith provided the strength to endure. The camaraderie among the prisoners was also a source of strength. They formed bonds that would last a lifetime, helping each other endure the physical and psychological torment of captivity.

The end of the Vietnam War was marked by the Paris Peace Accords of 1973, which led to the withdrawal of U.S. forces from Vietnam and the release of American POWs. Operation Homecoming, as it was named, was a significant and emotional event for the United States. It involved the return of 591 American POWs to their homeland.

Operation Homecoming was a moment of national relief and celebration. Families eagerly awaited the return of their loved ones, and the sight of former POWs stepping off planes and into the arms of their families was a poignant symbol of hope and resilience.

However, the transition back to civilian life was not easy for many of the returning prisoners. They faced challenges on multiple fronts. Physically, many had endured severe injuries and illnesses during their captivity, and their recovery would be a long and arduous process.

Psychologically, the POWs carried the scars of their imprisonment. They struggled with symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), nightmares, flashbacks, and emotional difficulties. Reconnecting with families who had changed in their absence also presented its own set of challenges.

Moreover, the broader backdrop of a nation deeply divided over the war added complexity to their return. While many Americans celebrated their homecoming, others viewed them with suspicion or even hostility. The POWs themselves had varying perspectives on the war, and some were openly critical of the U.S. government’s handling of the conflict.

The experiences of American POWs in Vietnam have left a lasting impact on the nation’s consciousness. Their stories of survival against the odds serve as a testament to the endurance of the human spirit. Yet, they also highlight the profound costs of war – not just in terms of physical suffering but also the lasting psychological scars that can persist long after the conflict has ended.

Organizations like the National League of POW/MIA Families were established to advocate for the fullest possible accounting of all missing personnel from the Vietnam War. Even decades after the war, efforts continue to locate and repatriate the remains of those still missing. This ongoing commitment reflects the enduring legacy of the Vietnam War and the POW experience.

The Vietnam War and the experiences of its POWs raise profound questions about the responsibilities of nations to their captured soldiers and the ethical boundaries in warfare. They remind us of the immense sacrifices made by service members and the profound resilience of the human spirit even in the darkest of circumstances.

In conclusion, the U.S. POW experience during the Vietnam War is a poignant chapter in the annals of military history. It offers lessons about the depths of human endurance, the bonds of brotherhood, and the complexities of war and diplomacy. Remembering and understanding these experiences is essential in honoring the sacrifices made and ensuring that such tragedies are not repeated in the future. The story of American POWs in Vietnam is a testament to the indomitable spirit of the human soul and a reminder of the enduring cost of armed conflict.