It was the worst prison camp of the Vietnam War. Lodged deep in the jungle west of Da Nang, South Vietnam’s second largest city, the prison camp—or camps, for it was a moveable horror—was not easily imagined by a generation that had grown up watching World War II movies. There were no guard towers, no search lights, no barbed wire. Instead, the camp consisted of a muddy clearing hacked out of the jungle where sunlight barely penetrated the interlocking layers of branches and vines. A thatched hut served as the prisoners’ shelter, a bamboo platform was their communal bed.

The 18 young Americans, barefoot, in tatters, and on the verge of starvation were given little rice and forced by the Viet Cong to gather manioc, their potato-like food, which was sometimes poisoned with Agent Orange by U.S. spray planes. They lived under constant danger of being bombed by their own forces. An American turncoat armed with a rifle—Marine Bob Garwood—helped the Viet Cong keep them in line.

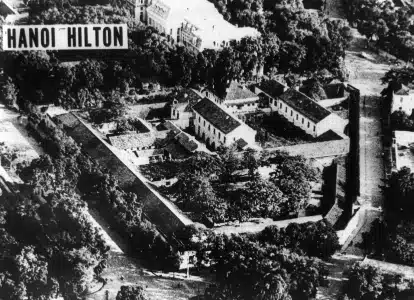

Twelve of the 32 prisoners of war who entered the camp died—almost forty percent. Five were freed for propaganda purposes. One defected. The remaining 12 American survivors, plus two German nurses, were saved only by the North Vietnamese decision to send them on a forced march up the Ho Chi Minh Trail to Hanoi in 1971, where they remained until they were freed with the 579 other U.S. POWs at the time of the ceasefire in 1973.

This story comes from my book SURVIVORS, first published by W.W. Norton in 1975 and still in print by Da Capo. I have edited and combined some of the material for this Internet adaptation. The men listed were all captured in 1968. In this excerpt, only one officer was among those interviewed—Warrant Officer Frank Anton, a helicopter pilot. The rest of the POWs were drafted infantrymen, though one of them, David Harker, had dropped out of college and another, James Daly, was a high school graduate and conscientious objector.